From Crisis to Chronic: The Normalization of the ADHD Drug Crisis

They insisted a month in that it would just be thirty days, maybe sixty.

Thanks for reading Beneath The Surface! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

In November, CNN reported that the FDA expected the ADHD drug shortage to last for two more months. The shortage was officially announced in October, but anecdotally people in the ADHD community began experiencing the shortages in August.

The crisis initially centered around Adderall, the go-to stimulant medication for managing ADHD symptoms. America’s most popular stimulant after coffee. As supplies of Adderall dwindled to the point of scarcity, the repercussions began to reverberate across the spectrum of ADHD medications. People accustomed to relying on a specific prescription suddenly found their familiar pharmaceutical lifelines snatched away. A domino effect ensued, with shortages spreading to other commonly prescribed drugs that individuals with ADHD had come to depend on. The ripple effect of the crisis magnified the challenges faced by those with ADHD, who were now contending not only with the symptoms of their condition but also with the stress and uncertainty of obtaining their necessary medications.

I have been taking Ritalin fairly consistently now for a decade and have experienced this firsthand. The reasons for the shortage are both multifaceted and also shrouded in some secrecy. Teva Pharmaceuticals and the DEA have been famously tight lipped about it, and describing it would be a large (perhaps future) piece in and of itself. Right now, I intend to describe the experience of being someone living through this crisis.

The process of getting ADHD treatment in the United States is famously not ADHD friendly. It is murky, difficult and counterintuitive. It is something you genuinely have to experience to understood how complicated it can be. Let me break down how it used to be, and how it is now. Let’s dive beneath the surface.

The Old Normal:

- Go through a comprehensive process with a physician who provides you a formal diagnosis of ADHD after several meetings with you, discussions with your family, and sometimes even testimony from your schoolteachers (if you are a minor, as I was when I was first diagnosed). Despite recent controversy with ADHD diagnoses being granted by Telehealth startups, the majority of those who are diagnosed with ADHD were pre-pandemic and was a much more intensive process.

- Great, you have a diagnosis! Now, begin a process of trial and error to discover which medication works for you and which dosage works for you. Every month, your doctor will write you a script for a different medication and you will go to the pharmacy to refill it. However, let’s assume you get your perfect medication off the bat.

- Your doctor writes you a script, you go to the pharmacy, and they fill it for you. Your doctor can send three months of scripts at a time to a pharmacy, so you need to meet with your doctor every three months. However, if you need to change where your scripts get sent, you must send your doctor a message on MyChart to make them aware of the change as pharmacies cannot transfer scripts between each other.

- When you need to refill your script, you can’t usually get your medication in advance of your medication running out. If I have 30 days of pills, I can get my medication 30 days after I last went to the pharmacy, or most insurance will try to block it.

- You must get your medication in person. You cannot have it mailed to you like you can many medications. Nobody except you can go pick up your medication.

All of this is during formally normal times. This is frustrating enough, but workable. But now, the New Normal.

The New Normal:

- Your doctor writes you a script.

- You call your local Bartell Drugs and say “Hey uhhh….you got any Ritalin?” They tell you they are not allowed to tell you that information over the phone, so you go to the Bartell Drugs and ask that in person, at which point they tell you “no”.

- You try to call your Walgreens and learn there are twelve callers ahead of you and hang up.

- You search stories from the community on Reddit on how to get information from pharmacies, and then you start calling pharmacies and confidently saying “Please give me methylphenidate 36 mg, extended release, please.” Then people start telling you over the phone that they don’t have the medication, so at least you no longer have to travel to that pharmacy.

- Even still, all of this is time, and energy, and if you have a job it can be money. Each pharmacy has an automated voice assistant filter that adds five minutes to the call. Each pharmacy often has callers ahead of you. They all have varying hours of being open, some are open weekends and some aren’t.

- You are one second away from calling pharmacies outside of your city when you finally break through to a Fred Meyer on the other side of town and find out they have your meds. Hooray! But remember, you need to have your doctor now send that script to Fred Meyer, so write that message.

- Your doctor is working in a collapsing healthcare system beset by horrific staff shortages and brutal working conditions so it takes her two days to fulfill that request.

- You go to Fred Meyer as soon as you get confirmation your script was sent over….and in that time, Freddie’s has run out of methylphenidate. However, we have a comprehensive guide on how to handle this situation. Simply scroll back up to step 1 and follow from there.

Misconceptions of ADHD:

One of the biggest misconceptions of ADHD is that it is a disorder of largely young boys who act up, run around with a lot of energy, disrupt social norms and can’t control impulses, and you give them Adderall as a way to calm them down.

This is a dramatic misconception that dramatically affects how people view this crisis. People with ADHD can be men, women or non-binary. They can be white, black, Asian, Latino, Native or any ethnicity. And they can be children, teens, adults, seniors. Children with ADHD will become adults with ADHD - we can infer this from a scientific theory called “time”.

And those adults are perfectly capable people who simply have a neurological difference that makes them more prone to executive dysfunction, time blindness and sensory overload amongst other symptoms. It is important to note that the severity of these symptoms is different for every ADHD brain1, just as it would be for the brain of someone without ADHD, who we’ll call “neurotypical” here. One of the common critiques by ADHD-skeptics is “everyone struggles with sensory overload or getting exhausted by tasks sometimes”, and that is true. However, the bar for what might cause overload or burnout for a neurotypical on average is higher than that for an ADHD brain.

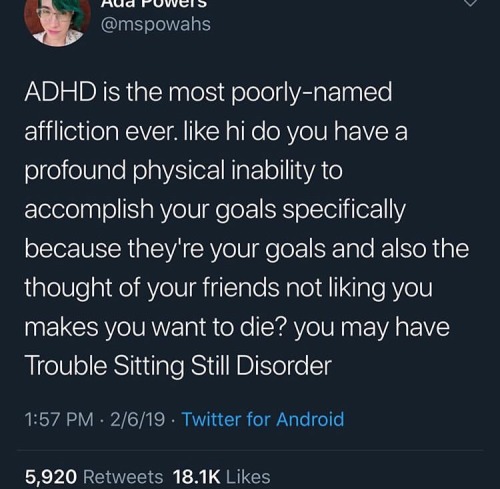

What this means is far more complex than just “hyperactive kid running around”. Frankly, I find the term “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder” a bit amusing because it’s a term created by the neurotypical community describing the behaviors that frustrate them. As a viral Tumblr post said “It’s so obvious they named it based on how we inconvenience them, rather than what it actually does to us”.

The Reality

In reality, ADHD can be brutal when living by the rules of a neurotypical society. ADHD brains are more likely to struggle with keeping jobs, housing and relationships than those without ADHD. It can mean missing work, chronic fatigue, distraction, disordered eating and disordered sleep. It can mean dangerous drivers on the road because fatigue or distraction hits at a crucial moment. It is, quite frankly, a public health crisis.

The ability to get on medication was a crucial part of treatment for ADHD brains. It is not the definitive cure. Picture a pyramid. At the base is the medication. However, on top of that base I had many other practices such as eating consistently, sleeping consistently, exercising, stretching, taking notes and forming to-do lists. However, all of this was dependent on the base. Once that went away, maintaining the pyramid upright can be next to impossible. Not only that, but like any substance your body does become dependent on the medication after a while and withdrawal effects can be brutal.

One of the best pieces about the ADHD drug crisis came from The New York Times, where they interview many adults struggling with the shortage:

Mr. Kenneally, who is a process technician at a biopharmaceutical company, worries about how he will work without medication. Deep-seated fatigue set in within just a few days of being off Adderall, he said.

“The people that depend on the medication for daily functioning, for going to work, for being a good mother, for going to class, are struggling,” said Fairlee C. Fabrett, director of training and staff development for the child and adolescent division at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts. “This is not something to make light of.”

…

Thomas Mandat, 24, who was diagnosed with A.D.H.D. in the third grade, hasn’t been able to fill his prescription for a month. In his first two weeks without medication, he was so exhausted he couldn’t eat; he forced himself to choke down protein shakes.

On his third day without medication, he sat down at his desk at a financial services company in Las Vegas and felt as if his head were filled with sludge. He described feeling as if he were in a “zombified” state: “It’s like if you sleep eight hours, but it feels like you only got three,” he said.

Not every patient who suddenly goes off Adderall will experience withdrawal, Dr. Fabrett said. But those who do may grapple with mood swings, irritability, appetite suppression and, in severe cases, suicidal thoughts. They might also experience headaches, jitteriness, intense fatigue and gastrointestinal distress, said Dr. Anish Dube, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Council on Children, Adolescents and Their Families.

…

Snezhana Kostornova, 31, a psychology student who was on Adderall until two months ago, has been struggling with rebound symptoms. A few weeks ago, she turned on her bathroom sink to hand-wash clothes but got distracted when she went to get soap; she watered her plant; then she started browsing for curtains online until water sloshed over her feet. Ms. Kostornova said she is just trying to get through the Adderall shortage day by day. She sometimes wears earplugs when she leaves home because the noises outside can be overstimulating, a symptom of A.D.H.D.

Ms. Kostornova isn’t sure how to plan for her future without a clear timeline for when the shortage will end. She wonders if she should postpone grad school. Should she tell her professors that she has hit a wall? Responding to texts from family and friends feels draining without her medication — should she explain that to them? “You just think, how much can you do without having your deck of cards fall down?” she said.

Without Adderall, Edward DiNola, 35, a game programmer and designer in Orlando, has become almost nocturnal; his sleep schedule is piecemeal and unpredictable. After a week without medication, he went to bed one day at seven in the morning. “It’s a bit of a curse to not have control over your own energy,” he said. He was diagnosed with A.D.H.D. in his early 30s and found that Adderall “is like glasses for my brain,” he said. “It brings me into focus and gives me a little more control.”

Having taken Adderall for the last 12 years, Natalie Rotstein, 24, who uses they/them pronouns, said that being unable to access it is “a safety concern.” They have been tightly rationing their doses over the last month, scared that one day they won’t be able to refill their prescription. They’re scared of blowing through a red light while driving through Los Angeles; at their neuroscience research job, they worry about forgetting to warn patients to take off jewelry before going into the MRI machine, which can cause skin burns.

In October when I first couldn’t get my medication at my local Walgreens, I spent three weeks frantically calling every pharmacy in Tacoma, Washington to no luck. While I waited, the withdrawal symptoms set in. Initially it was an ADHD rebound - huge hyperactivity and a lot of nervous energy. But then it became deep-seated unshakable fatigue and aches throughout my body. For two days it became incredibly difficult to move. I was either in bed or on the couch, and I remember feeling grateful for gloomy Washington autumns as looking at bright light for too long felt overloading.

Throughout it all, I was lucky. I worked from home so I could take time to rest. I could build my workplace around my needs. My team lead at my last company was very understanding when I disclosed my ADHD and we built a plan together to allow me to work as best as I could under the circumstances. And because I worked from home, it was easy to take time to call pharmacies while writing code, which someone struggling with the crisis working in food service or retail could not do.

Right before Thanksgiving, I finally broke through to a pharmacy in a rural Washington town called Shelton an hour’s drive away. My girlfriend drove me out to Shelton as I am a poor driver even with medication, let alone without, and I lack a car. It was a big burden to place on her for something I should be able to get at my local pharmacy a ten minute walk away by myself. I am grateful for the support system around me but cognizant at the difficulties imposed on them when I do need the support. The crisis affects ADHD brains the most, but the neurotypicals we love around us struggle as well.

It Shouldn’t Be This Way. It Shouldn’t Have Been This Way.

The crisis has been a rollercoaster of frustration, exhaustion, and uncertainty that can at any time reshape my daily existence for an untold amount of days in a month. The initial reassurances of a short-lived setback quickly dissipated, leaving us trapped in a perpetual struggle for access to the medications we so desperately rely on.

The impact of this crisis reaches far beyond a mere “inconvenience” for some children and their parents (who matter just as much, and for whom it is often far more than an inconvenience). It infiltrates every aspect of our lives, disrupting our work, straining our relationships, and plunging us into the depths of physical and mental fatigue. The withdrawal symptoms, the relentless search for pharmacies with stock, the endless phone calls, and the mounting anxiety—it all takes an immeasurable toll on our well-being. This is not just a matter of navigating the complexities of obtaining medication; it is a profound public health crisis that demands immediate attention.

The crisis has illuminated the need for ADHD treatment to become much simpler and streamlined. ADHD brains need to be given accommodations at work during shortages. They need to be able to be trusted to get their medication by themselves rather than having to have quarterly doctor’s visits. Insurance shouldn’t try to gatekeep your medication from you or suddenly decide one day they won’t cover one particular medication or the generic, but will instead cover a very specific brand name pill. You should be able to send your medication from pharmacy to pharmacy instead of having to have your doctor re-send a script each time if you need to go somewhere else.

And most importantly, we finally need more supply and more transparency. To quote a fantastic piece by Wilfred Chan of the Guardian:

In recent months, patients have reported problems filling nearly every type of ADHD medication. What’s stranger is that no one seems to know why. Is it some kind of supply chain issue? A pandemic-era surge in demand? A government crackdown? Official explanations have offered little clarity. The FDA’s announcement mentioned “intermittent manufacturing delays” at Teva, the producer of the branded version of Adderall, but few other details. The American Society of Health Pharmacists reports shortages of multiple ADHD drugs but says manufacturers have given no explanation.

Meanwhile, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which controls the supply of the drugs, announced last month that it would not increase manufacturing quotas for 2023, despite the shortage – again, without providing a reason. One congresswoman, Abigail Spanberger, wrote to the DEA and FDA to demand an explanation last December, but Spanberger’s staff told the Guardian she had yet to receive a response.

The situation has left patients in turmoil. Since the mid-2010s, adults have overtaken children in receiving prescriptions for ADHD drugs. Studies show stimulants offer dramatic benefits to ADHD patients, improving their performance at school and at work, and reducing their risk of depression, anxiety, substance abuse and suicide. A 2017 analysis of millions of patient records even found that adults with ADHD taking stimulant medications were far less likely to get into a car crash.

The millions of adults in the USA with ADHD have been struggling for a long time. But this past year has been something else, and something incredibly difficult. The crisis will require systemic changes from major corporations and government agencies, but it also requires dismantling beliefs that affect how neurotypicals view ADHD brains. When the stereotypes are dismantled and we are given the resources we need to succeed and be autonomous, we can all can thrive.

This week after two weeks of struggling, I was finally able to get my medication from Bartell Drugs. I hope next month I’m only struggling for two days. Until then, I’ll refrain from taking my meds some days so I can stockpile for the bad times.

Book Suggestions

Thanks for sticking with me through this piece. Before I go, I want to recommend two recent books I’ve read and greatly loved.

The first is “We’re Not Broken: Changing The Autism Conversation” by Eric Garcia. Garcia is an autistic Washington Post reporter who chronicles the history of autism diagnoses in the US, the misinformation surrounding the diagnosis, the stigma faced by many with it, and the lives of autistic people as told by autistic people. There is a lot of overlap between autism and ADHD and I tremendously enjoyed this book and the variety of people whose perspective it showed in a thoughtful and empathetic way.

The other book is “Under The Sky We Make: How To Be Human In A Warming World” by Kimberly Nichols, which I bought from Powell’s in Portland a few weeks ago. Nichols is a climate scientist with a wicked sense of humor who has written an excellent and engaging read that I did not want to put down, and am in fact on my second of. Nichols implores us to find purpose in a warming world, and this book has encouraged me to find ways to improve my own carbon footprint and take further action. I highly recommend it.

Thanks for reading. Please feel free to subscribe for free if you haven’t. Until next time.

Thanks for reading Beneath The Surface! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Calling people with ADHD “ADHD Brains” was an idea by popular ADHD YouTuber Jessica McCabe of “How to ADHD”, which I love. ↩